Created 21.x.21, tweaked reference 20.iv.22 to reflect paper coming out in bound issue of the journal.

This follows on from: Recent papers with perspectives on CORE translations (1) Di Biase et al., 2021 as part of a series of posts that I hope will throw helpful light on the translation of self-report mental health/well-being questionnaires. I hope the posts, through the perspective of translation, will also throw light on problems with much current thinking about the psychometrics of these measures. These are issues that are generally ignored.

OK, our paper is:

Yassin, S., & Evans, C. (2021). A journey to improve Arabic‐speaking young peoples’ access to psychological assessment tools: It’s not just Google translate! Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 22(2): 396-405. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12431.

As we were both working on this for free we couldn’t afford to pay for open access but if you want a copy just contact me. Whereas Di Biase et al. 2021 comments on some of the issues with prevailing quantitative psychometrics, this paper has only simple numbers of young people who helped the work: it is essentially qualitative.

Background

As that title of the paper says, this was a narrative about a journey: about following the map or GPS of the CORE translation protocol but also about knowing that what we wanted was not just as good a measure for the purpose as we could create, but also a measure that will, like all measures be used in contexts and here the first target context was that of first language Arabic speaking young people in the UK educational system: a context buffeted by some real issues. As metaphor that translation protocols are maps or GPS suggests, they help you get where you want to go, but to get there well you must know why you want to go there and understand the destination and the challenges en route. Blindly following a protocol without knowing your aims and the context you bring, and without thinking deeply about the contexts in which the measure will be used, is likely getting on an underground (subway) train and believing that the fact that it has a map means you will automatically come up at the right place. Good protocols help our journeys but we must look around, really think about where we come from and where we are going, to get the best translation.

So we were following the CORE protocol but we were bearing in mind the language issues for Arabic and its crucial cultural connotations both in the UK and around the world. Any good translation of a measure starts with the qualitative but prevailing ideas about self-report measures, and particularly prevailing psychometric diktat, tries to bury the qualitative and subjective in numbers. To me this seems bizarre given that our hope is that the numbers will tell us a bit about the intrinsically utterly subjective issue of what is going on inside one person’s head.

Prior to this paper, the nearest I had come to describing the qualitative processes of a CORE translation was the excellent (honestly, I don’t say that about all my papers!):

Rogers, K. D., Young, A., Lovell, K., & Evans, C. (2013). The challenges of translating the clinical outcomes in routine evaluation-outcome measure (CORE-OM) into British Sign Language. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 18(3), 287–298. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/ent002 (open access here).

However, that paper focuses on the fascinating and vital issues that translating for an oral/written language to a signed language creates so the generalities of translation were secondary there to that very particular set of challenges.

However, all translation has challenges. Going back to the previous blog post: Italy has only relatively recently become a single nation state and dialect variation across Italy is larger than for many languages; that was something we tried to address with the Italian translations of the YP-CORE and CORE-OM. However, that language variation is small compared to that across the Arabic speaking world as Arabic is used across many very different countries and is intrinsically linked via the Quran to Islam in a way that is fundamentally different from any links between Italian and Catholicism or to Christianity (or between the English language to protestant Christianity through the King James and subsequent bibles). Sula and I were very aware of these challenges and we chose to write the paper as a personal one, at times with separate “Sula” and “Chris” threads in order to address how our fairly different personal histories and experience brought very different perspectives to the work. Perhaps we were fortunate that one peer reviewer clearly liked this and read it from the largely qualitative perspective we had hoped for while the other, though certainly being constructive and trying to be even more so, really wanted the paper rewritten in a rather different, impersonal, much more traditionally psychometric way. We were able to steer between the two enough to keep what we wanted (including the title!)

Translation process

One starting point was a lot of discussion, both between ourselves, and with others who speak Arabic, about language variation and a fair bit of reading about this. Much of what I read seemed polarised between those who clearly want to minimise the extent of variation, and those who perhaps want to amplify it. Given that we wanted a translation that might lean on Modern Standard Arabic, and perhaps Cairo and Al Jazeera Arabics, but one that would not seem alien across as many countries as possible, we knew had a challenge (and no money!)

As a result 29 young people with roots in, or connections from, 11 different countries contributed independent forward translations. The focus group stage in which the various translations were reviewed involved 13 young people (with two Arabic speaking adults and myself there for the questions about why certain items in English are as they are). The last stage of qualtitative field testing involved 21 young people. Sula and colleagues did a brilliant job of trying to cover as much probable language variation as we could.

The first, forward translation phase resulted in between 24 and 29 different versions of the various components of the measure (10 items, the introduction, the time frame and the response anchors). Twenty-nine versions from 29 people says that for some components no-one agreed with their translation. You can also see that the number of agreed translations for any component was small even when it wasn’t zero. In fact, as has been the case with all CORE translations, many of the differences were small and were linguistically, even culturally, unimportant and a choice between them could be made fairly easily by the group. More challenging however some differences related to age language abilities (in Arabic or in English) and had to be considered very carefully. That has been an issue for all YP-CORE translations done mainly by young people. Probably another set of the differences related to language variation but our focus was not to map that but to find a good enough, perhaps a “least worst”, version that made sense to all or nearly all.

The focus group worked hard on the many differences (seeing them on a screen) and some items proved easier than others to resolve to a single preferred translation. The first item took nearly an hour to resolve. That was partly because it was the first and the group were having to settle into how all voices would be heard and how to cope with the challenge. However, it was also because the word “edgy” was generally agreed to have no equivalent in Arabic and to be very hard to translate. By contrast, item 9 only took five minutes and item 10 seven minutes.

The qualitative field testing involves participants being asked to imagine how someone they knew who might have had problems or stresses might read the questionnaire and what that person (and, implicitly, the participant) might have understood each component. That ended up happening in two phases as the first participant suggested two changes, to two items (1 and 9), that seemed very likely to be improvements and these were offered to the next ten participants for an alternative to the wording that had come out of the focus group. All ten of those participants preferred the newer versions. Consequently the second phase of another ten participants used only the improved translation.

Final Sula obtained two back translations by people who had not been involved before and had never seen the English YP-CORE. Following which Sula and I discussed the slight differences between the back-translations and the original and all the issues that had come up in the field testing. Sula of course had to try to explain to me in English all changes but we felt she had succeeded in doing that. Then the only remaining challenge was for me to copy and paste RtL (Right to Left) language text that looks beautiful but means nothing to me, into a revised YP-CORE InDesign file to get a to a final PDF.

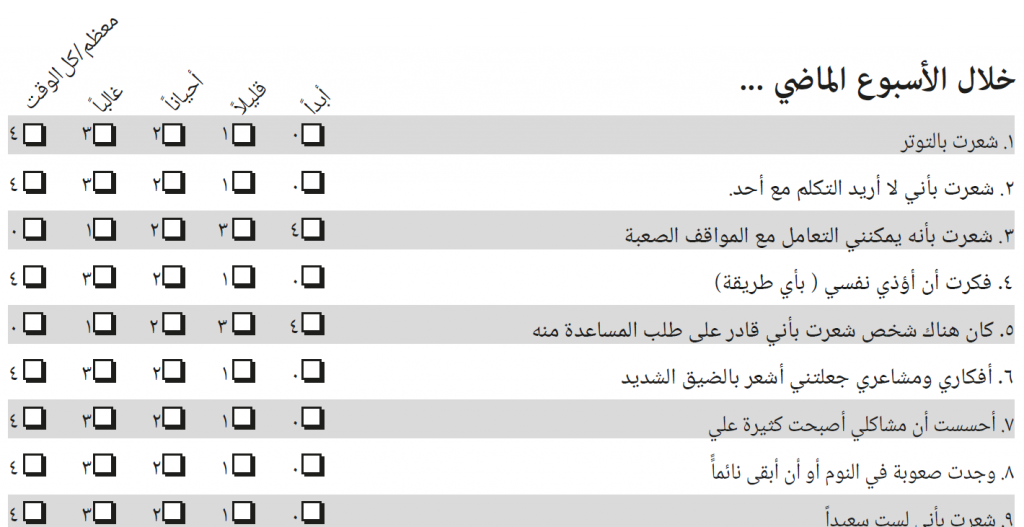

Actually, that wasn’t quite the end: then there was the question of the numbers on the response boxes, see the Arabic YP-CORE page to understand more about this but we currently have three options.

Versus:

Summarising

Clearly this was a huge piece of work (and we are deeply grateful to all who gave their time voluntarily to make it possible). I am not saying that the CORE protocol requires these numbers of participants for any YP-CORE translation: it doesn’t. It certainly doesn’t require this many for CORE-OM translations (where you have far less of an issue of age differences to mangage). However, I argue that the old translation/back-translation procedure with a handful, or even just two translators, is dead. In the protocol-as-map-translation-as-journey metaphor, that’s not even going by underground, it’s probably worse than than just feeding the original into Google translate.

I am arguing that the heart of any translation of any self-report measures is a qualitative enterprise. It is work that draws on qualitative not quantative methods and epistemologies. That is certainly true of the CORE translation protocol and, though usually implicitly, of all modern translation protocols. What quantitative psychometric explorations, “validation studies”, add after a translation has been done is important but can never rescue an insufficiently thoughtful translation. One huge problem with the marginalisation of translation complexities and the idea of “validating the measure” is that it perpetuates the myth that self-report questionnaire scores are like the scores from a blood test or from standing on a weighing scales: they’re not! I’ll come on to that next in this series of blog posts.

Images, viewpoints and perspectives

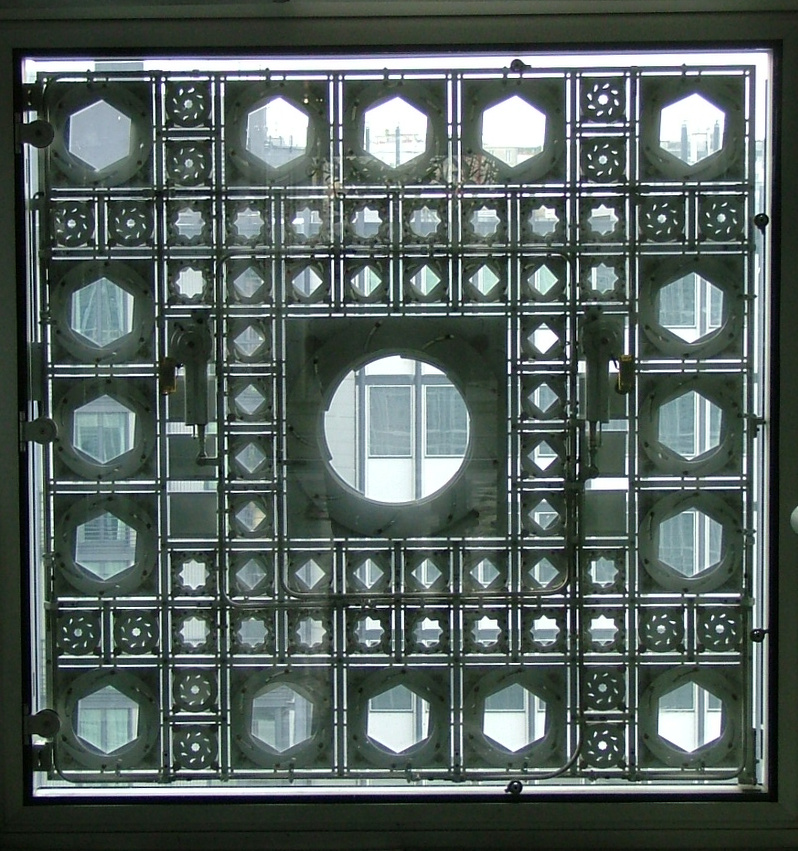

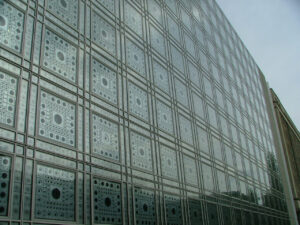

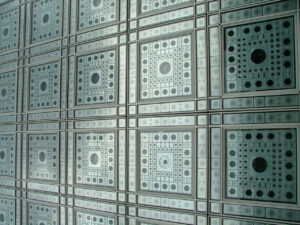

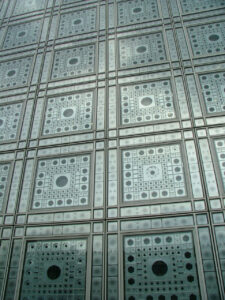

That header image? From a 2011 visit to the wonderful Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris. Try flicking between https://www.imarabe.org/en, https://www.imarabe.org/fr, https://www.imarabe.org/fr and https://www.imarabe.org/ar to compare languages (much of the text in the Arabic version remains in French but the Arabic is there for major headings and for things that change rarely). There are much better images of the amazing shutters on that site too, but here are a few more of mine. I do like playing with perspectives. You should be able to click on the images to see them full size.